PARAGUAY: 5 CHALLENGES OF A SOCIABLE CYCLIST

I’ve been thinking a lot about what could be interesting for people to read who are not here with me. I keep meeting people every single day, but how to share all this? How to turn this experience into something more universal? These questions that have been running through my head over and over ever since I started my trip. But then I met Cesar. A professional blogger from Asunción, Paraguay, whose one and only advice to me about blogging was: write what you care about. And although I would love to write about the people I’ve met, right now I feel like sharing the challenges I’ve been facing while meeting them. Don’t get me wrong, I’ve been treated like a queen in Paraguay, but for some reason, the start of my second trip has drained a lot more energy out of me than expected. So, why not go ahead and tell about it? (Later on I will surely tell more about the people!)

1. Sexist comments

Paraguay is known for being a culture way more macho than e.g. Uruguay or Argentina. The men I’ve stayed with and spoken to personally have all been extremely nice and polite. Yet, when cycling I can’t seem to avoid sexist comments. I know I look exotic here. I have blue eyes and ‘blond’ hair (I don’t think I’ll ever get used to being rubia, as in Finland I’m considered a brunette). So, just imagine how exotic I look cycling down the road with a fully loaded bicycle. Men stare, road workers shout. And I’m getting used to that. In fact, if I yell a cheerful hola! or adios! before they say anything, that usually disarms them. However, what I can’t get used to are the men who seem completely “civilized” and then turn out to be something else. They walk up to me and start asking me basic questions about cycling, such as “how many kms do you ride per day?” or “where did you start your trip?”. Then, all of the sudden they stare at me with a greedy look in their eyes and say things like “you’re legs must be in great condition” or “you look very good on that bicycle” or “if you had a husband, he’d probably love to cycle behind you”. C’mon, seriously? It’s neither flattering nor funny. I just want to cycle. And while doing it, I really don’t need any random men commenting my appearance or my condition. Fortunately, everyone here keeps telling me it’s only words, never action.

2. Vegetarianism

Any vegetarian will know that it’s not always the easiest ideology to travel with. Not to Spain, not to Italy, sometimes not even to Northern Finland. It can be a real pain to tell people who invite you to dinner that you won’t be eating their lovely steaks, but that it’s no problem for you to just eat the side dishes. However, in the countryside of Paraguay, meat is such an important part of a meal that every single time I have been invited for dinner, people have prepared the best possible fish for me (which I do eat).

I’ve been a vegetarian for 21 years now (I do eat fish and seafood, but I’ll just go with this word) and during the years, I’ve gotten very used to explaining to people the reasons why (I don’t like the way animals are treated, I don’t like the taste of meat and I think we don’t really need meat). When living in Poland, I received some good training for this, as the Polish cuisine is mainly based on meat. In Namibia, I kindly refused to try biltong (dried meat) no matter how my friends tried to convince me otherwise. And in Latin America I survived the country of asado (barbecue), Argentina. But now, in this country where soy is cultivated yet not eaten, I have often been just near to an outburst explaining that a sandwich with “jamon y queso” is not vegetarian. And although I sometimes do consider eating meat out of courtesy, I just haven’t been able to bring myself to it yet. So, where is the line between being a disgraceful guest and sticking to your ideals?

3. Servants

I come from Finland and I’m just not used to servants of any kind in my home country. Some people do have cleaning ladies come in every once in a while, but no one I knows has an actual daily servant. Yet, whoever has ever lived outside Europe knows that servants are no rarity elsewhere in the world. I remember a Finnish friend of mine once telling me about her first high-school exchange day in Mexico: as she entered her new home and was introduced to all the people there, she immediately went and gave cheek kisses to everyone – even the maid. This was a huge scandal and she was told never be repeat that kind of behavior again.

Here in Paraguay, house maids are often referred to as “the lady who helps me out with cleaning/in the kitchen”. They come in in the morning and stay for the whole day in order to fulfil the needs of the families. They run to the shop, wash the dishes, wash the clothes and clean the house. They are workers who do not usually eat or drink tereré (cold ‘mate’) with the family, although this depends on the situation and the relationship the family members have with their “helpers”. Why does this bother me? Simply because I feel strange about someone else washing my dishes and cleaning up for me! Especially, because it’s only a very small, well-off portion of the population who can afford this kind of services.

4. European stereotypes

In Latin America, Europe is either frowned upon or glamorized. The media offers very interesting images to choose from. Many people here think it’s the most xenophobic continent on earth (which I agree with) and a continent, which still looks down on all others (which I agree with as well). But then, there are those who think everything in Europe is splendid. Those who think there is no crime and no sexual harassment, for example. So, when I was taken by car to a poor neighborhood to see worn-down houses and poor living conditions as a touristic attraction (I did not ask for this) and my host asked me what I thought of all this, he was confused by my answer: poverty is no rarity in Europe neither. Maybe it is in Northern Europe, but not in the East or the South. This surprised him and most people I tell about Europe, because people hear things they don’t expect. Such as, that there are indigenous people also in Europe. Or that not all Europeans are rich. Of course, poverty in Europe is not on the same scale as here, but still, there is poverty in Europe. And rapes. And robberies. So, being treated like a naïve European can sometimes be frustrating. I’ve been living in a neighborhood in Poland where it wasn’t the best idea to walk around alone at night. I’ve been living in Milan where you keep your handbag close to you in a metro. I’ve been living in Finland where my bicycle has been stolen from in front of my house.

5. Work

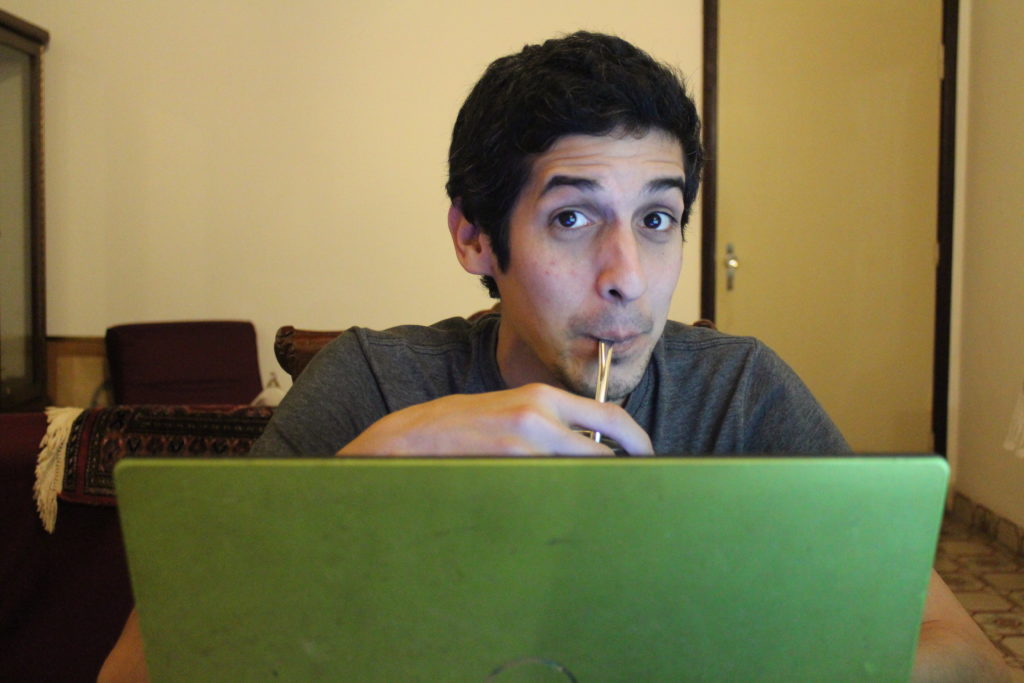

Writing, cycling and staying with people is not the easiest combo. When I cycle, I’m often extremely tired and all I want to do when I get to my destination is rest my mind and body. If you stay with people, you want to talk to them as well and if they’re Paraguayans, they’ll probably want to show you around. Because people here treat guests like royalties and really take time to make them feel special and welcome. So, if you also want to write, you have to either cut down on the cycling or on the social interaction. And although I could work at night, a cyclist also needs huge amounts of sleep. Then, when to write? When to have those creative moments of scribbling down something? How to combine being online and being in the now? This is the one and only challenge I know I can figure out. With time, I’ll come up with something. But luckily for now, there are moments like this where my couchsurfing host also needs to work and I can just sit still and write. And at the same time, I get new ideas from him concerning my blog. Like the latest: we just installed my Instagram account to be shown on my blog (a small add). I’ve loved doing it, so hope you’ll enjoy following it!

Who is Cesar, the inspiration to this article?

Cesar Sanchez is a wizard of social media, blogging and web content creation. He’s my couchsurfing host here in Asuncion.

Great stuff! I enjoyed reading it and I am looking forward for the future stories from your trip 🙂

Hi Kaisa! Thank you! I’m sure there will still be much to read and write about 😀

Hello Sissi, ok, welcome to my country!!!! It’s enjoyable to read about your impressions, you know, when one lives in a country, only a foreigner can realize some things that are normal for who lives there. Is good to know you are having a good time here, and also I see you know to see local realities, and you see important things. I wish your travel through Paraguay continues this way, Anything you need count on me. Happy cicling!!!!!

Hey Julio!! Thank you so much! I’m happy to hear you enjoy reading about my adventures 😀 They’ll surely continue, maybe not in Paraguay for long anymore, but also in other Latin American countries soon! Thanks again for your message and hope you’ll be cycling with me also in the future! 😀 Sissi